Why do we need to think about overheating in residential builds?

Building homes in which the internal temperature can be maintained within a range that is comfortable for the occupants isn’t just about what’s desirable, it’s about what’s essential for health and wellbeing.

Almost 900 pensioners died last year between the end of June and the end of August, because of heat waves in Britain1 – many of these deaths could have been avoided if houses and care homes were built to stay cool.

The Committee on Climate Change has estimated that mortality rates arising from overheating could, without any adaption from the population, rise from a current average of 2000 per year to 7000 per year by the 2050s.2,3

The Chartered Institute of Building Service Engineers (CIBSE) defines overheating in a building as when the local indoor thermal environment presents conditions in excess of those acceptable for human thermal comfort or those that may adversely affect human health.

Who is at risk?

Everyone, but, the elderly and vulnerable, including babies and very young children, are at a higher risk of death due to buildings overheating. Individuals with a lack of mobility are at risk as they may not be able to rehydrate or move to a cooler place/change into cooler clothing as easily. As architects, engineers and developers designing and building the homes of the future, it is our collective responsibility to mitigate this risk.

Why is overheating such a problem?

In line with zero carbon targets more and more new homes are being built with greater energy efficiency in mind. High levels of insulation are used to prevent heat loss and reduce heating requirements and more daylighting has been incorporated into contemporary builds to reduce energy consumption from artificial lighting.

Building homes and offices to keep heat in works well in the winter, but what about the summer when solar gain is high? In well-insulated buildings, internal temperatures can rise to uncomfortable and harmful levels as heat becomes trapped. In summer, even where occupants can open the windows, there will be little or no cooling effect when outside temperatures are as high or higher than internal spaces.

With building regulations having stringent measures on acoustics and air quality this can result in residents not being allowed to open their windows – some buildings are designed so that windows cannot be opened at all. This works to keep noise and polluted air out of the internal spaces but decreases opportunity for natural ventilation and cooling.

This is a bigger problem for city dwellers where noise and air pollution levels are much higher than in rural areas – even at night, occupants aren’t able to open windows to freshen their living and sleeping spaces with cooler air.

In urban islands, such as central London, which combine a higher risk of overheating alongside higher levels of noise and air pollution, this can cause design tensions – when one factor is adjusted to acceptable levels, another factor can change to unacceptable levels, for example, someone opening their window to cool a bedroom may not be able to sleep due to traffic noise. Sleep deprivation in itself is detrimental to health and productivity.

If a building is too well insulated, this can reduce energy bills in winter but for the summer months occupants may need to spend money on fans and perhaps have air conditioning (AC) units installed. AC consumes a lot of energy, so will increase energy costs and can also impact the health of residents by causing dryness of skin and respiratory problems.

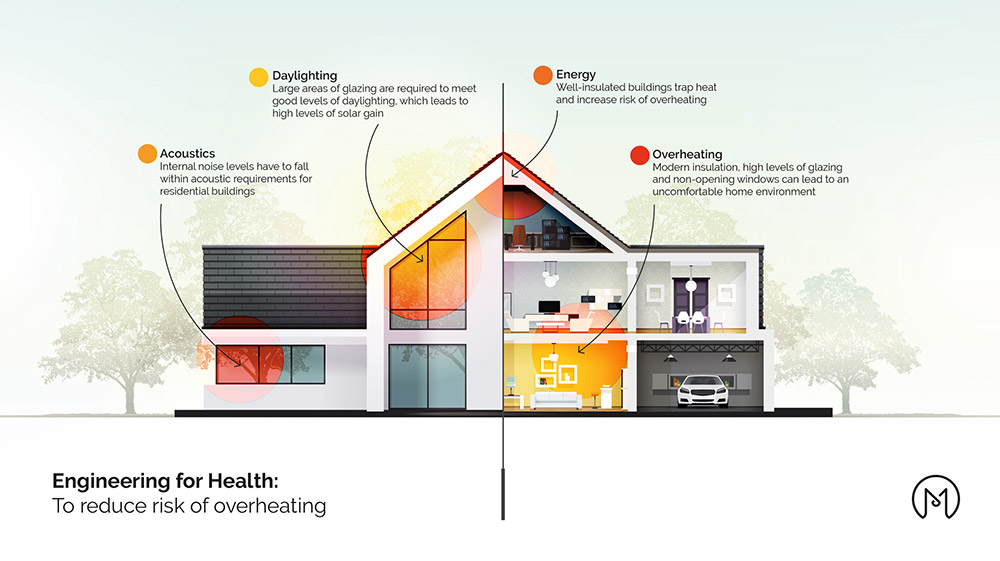

Factors to consider

There are a number of competing demands to consider in a residential build that need to be balanced by careful planning and design:

- Acoustics – internal noise levels have to fall within acoustic requirements for residential buildings: this can mean windows may not be openable as would allow too much noise, so cooling via windows is impossible.

- Daylighting – glazing installed to allow sufficient daylight to penetrate into rooms: but, too much glazing, especially on south-facing buildings can lead to high levels of solar gain and increase risk of overheating.

- Energy – buildings need to be well-insulated to prevent heat-loss and reduce the use of heating systems thus reducing carbon emissions: however, well-insulated buildings trap heat and increase risk of overheating.

- Overheating – buildings need a way of letting excess heat escape to prevent occupant discomfort. If a building is very well-insulated, has windows that can’t open due to acoustic requirements and has high levels of glazing to satisfy demands for daylight, occupants are at increased risk of overheating.

What can we do?

Passive methods to reduce overheating, such as opening windows and doors and closing shutters and blinds, are the most desirable to reduce risk of overheating, but these cannot always be achieved.

Overheating needs to be taken into account at the design stage of a building. Retrospective cooling is a lot more costly and less energy efficient, therefore buildings with higher risk of overheating are less desirable to live in and will be less profitable for developers in the long term. As temperatures increase due to climate change, the risk of discomfort and death due to overheating will increase; assets will devalue as people choose not to live in buildings where they cannot maintain a comfortable temperature.

At Milieu, many of us are chartered with the CISBE and we have been carrying out overheating assessments for years and consulting with architects and developers to mitigate risk. Guidance for overheating has recently become stricter, with new methodologies published by the CISBE in 2017.

The aspect of a building is usually fixed, with south-facing, single-side apartments tending to be at highest risk of overheating due to lack of cross ventilation and the fact that occupants do not have a choice to move to the cooler side of the building. The facade of a building, acoustics, daylighting, energy efficiency, heating, cooling and ventilation are all factors which, when taken into consideration at a very early design stage can be balanced to provide comfortable living and working spaces for occupants.

The future: managing the competing demands of residential design

Carl Carrington, CEO Milieu says, “every development is unique and requires individual consideration. We find that the most efficient and cost-effective way to address the competing demands of design is for building service engineers to be involved from the initial stages: early engagement with architects and developers to understand the challenges of a development and to assess risk of overheating, are essential to provide healthy living spaces, reduce risk of ill health due to overheating and reduce long term costs associated with retrofitting cooling solutions”.

—

At Milieu, we’re passionate about creating healthy spaces and making the environment of the building as healthy as possible for the people who occupy it.

To find out more about the services we offer and how we can help you make your building healthier, please call us on: 020 7183 3943 or email: info@milieuconsult.com

—

Sources:

1. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2020/01/07/nearly-900-pensioners-died-british-heatwaves-last-year-experts/

2. Climate change effects on human health: projections of temperature-related mortality for the UK during the 2020s, 2050s and 2080s Shakoor Hajat et al

3. https://www.cibse.org/knowledge/knowledge-items/detail?id=a0q0O00000DVrTdQAL

6-12 Manor Road | Stoke Newington

The scheme comprises a new build mixed use development in London Borough of Hackney designed by Ayre Chamberlain Gaunt Architects.

Horsell Moor | Woking

This scheme provided 34 high-specification retirement homes of one or two bedrooms. The four storey horseshoe-shaped building surrounds a south-facing courtyard inspired by the nearby common. Designed to make the most of natural light the double aspect apartments have floor to ceiling height glass windows.